Solutions for our homes

Solutions for our homes to help clean the air

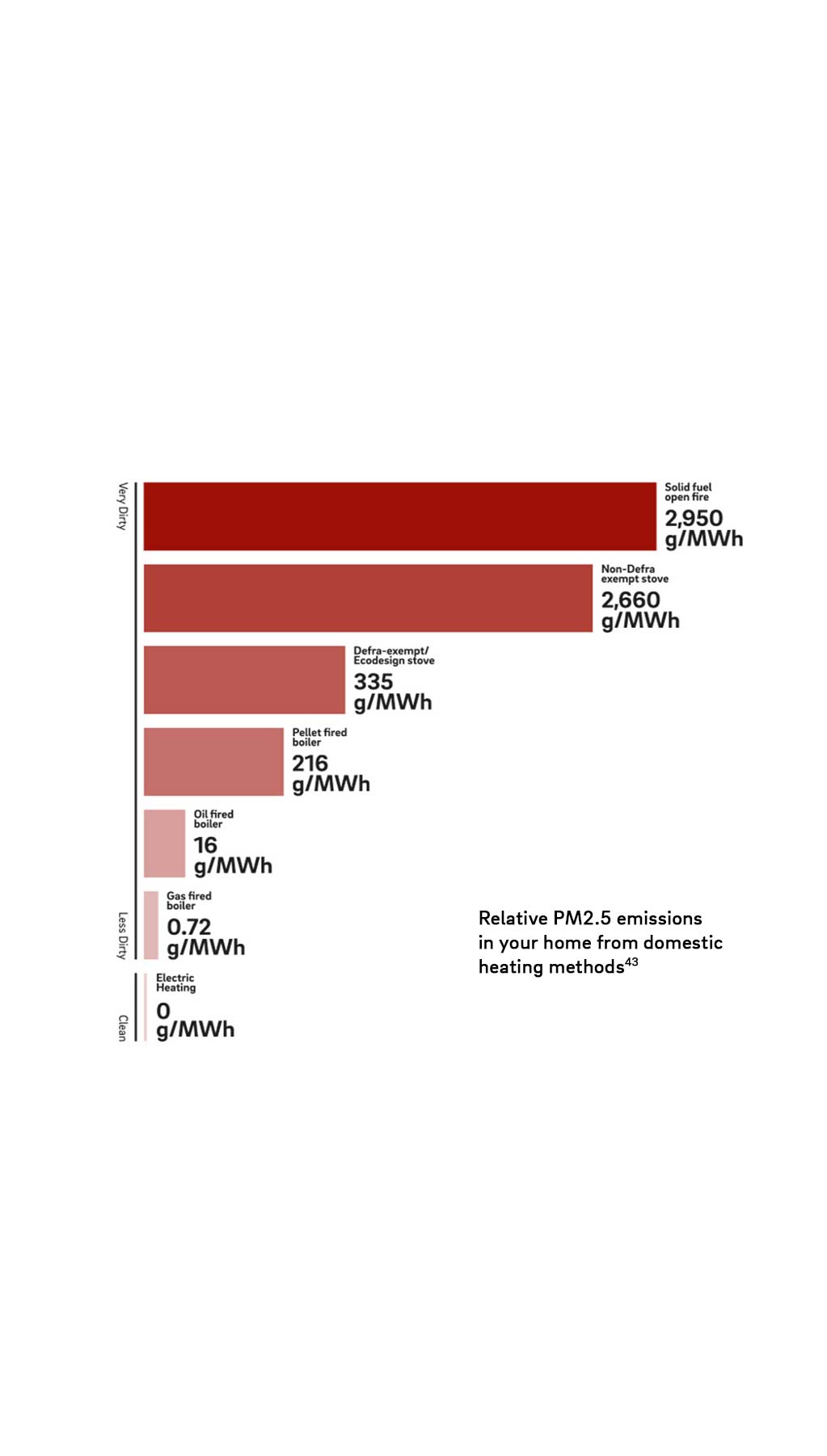

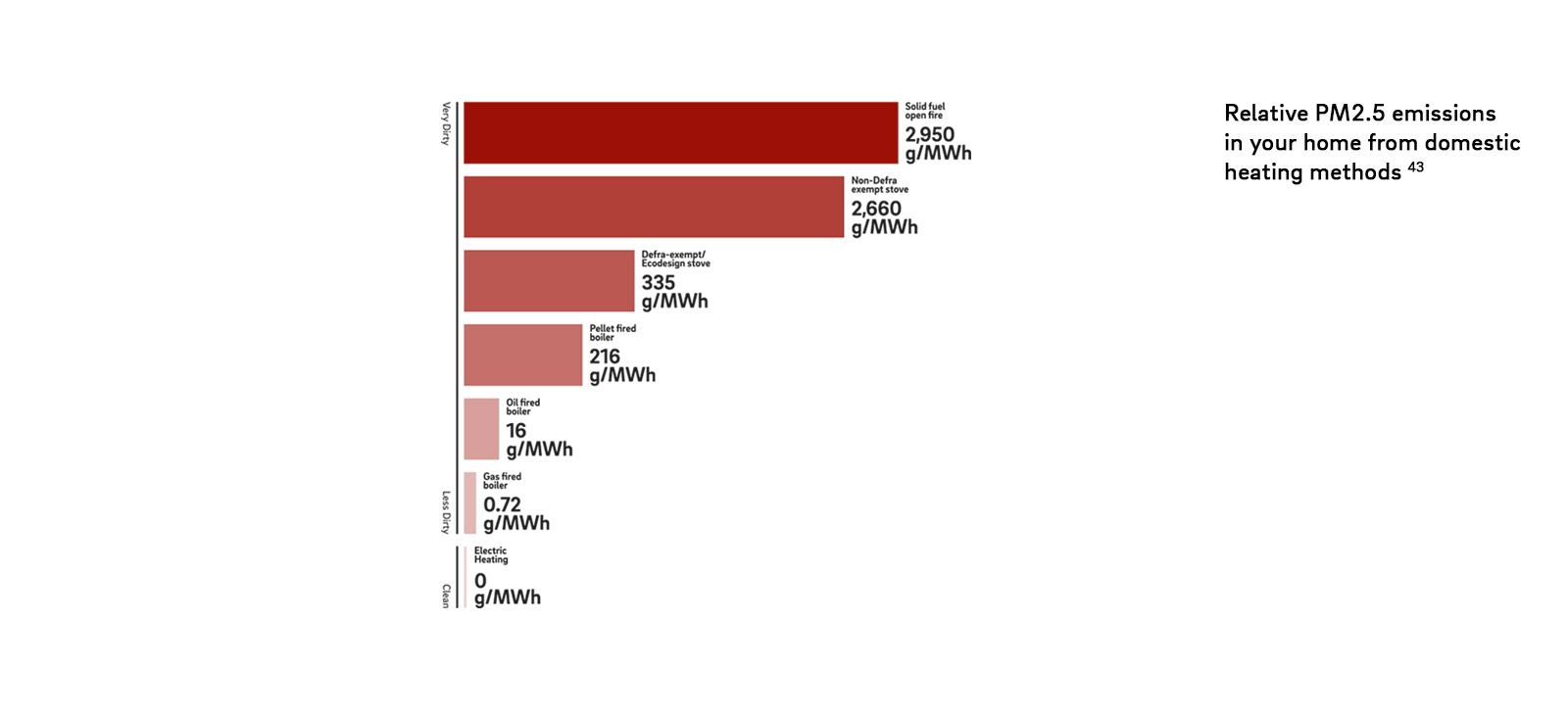

The connection between air pollution and the energy we use at home or work isn’t always obvious. Nevertheless, the way in which we heat our homes can ultimately impact local air quality. One of the principal forms of indoor air pollution is particulate matter (PM) which is produced by many forms of home heating. The increasing popularity of burning solid fuels in our homes is having an impact on our air quality and is now the single largest contributor to PM emissions.

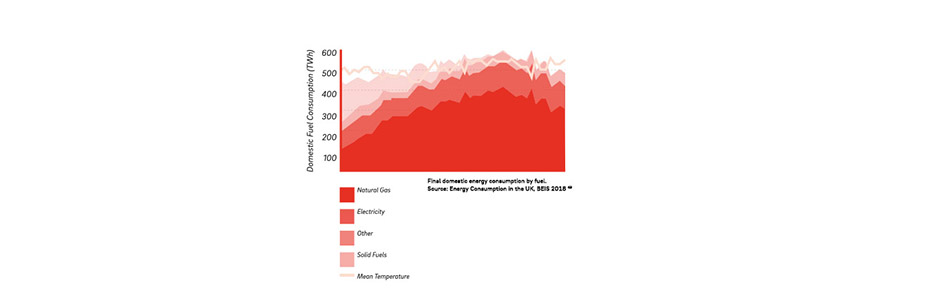

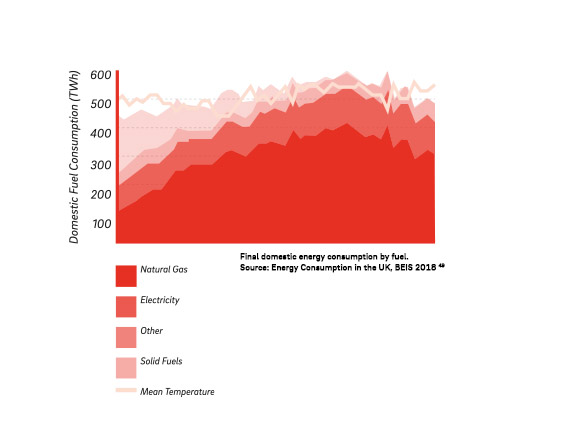

Homes account for 28% of all UK energy demand,42 putting them on the front line in the push for lower emissions.

However, the dominant form of heating in the UK is gas boilers, fitted in the vast majority of the UK’s 28 million homes.44

NOx emissions are produced from gas boilers and from September 2018 the Energy related Products (ErP)45 Directive set a maximum NOx emissions level for natural gas and LPG boilers of 56mg/kWh, with a higher limit of 120mg/ kWh applied to new oil-fired boilers; however, older heating systems will typically emit much higher levels of NOx.

Around half of the UK’s electricity demand is still met by fossil fuels,46 so turning on a light or using a hairdryer adds incrementally to the UK’s need to generate. And almost every time anyone takes a shower the water is heated by a gas boiler, which emits NOx gases.

Improving the energy efficiency of millions of houses, and transforming how we live in them, will translate to a direct lowering of NOx, CO2 and other pollutants.

Put simply, our homes are often the problem. The Committee on Climate Change’s latest progress report to Parliament stated that “all of the key buildings policy gaps identified in our 2018 progress report remain unaddressed or only partially met”.47

However, there are available solutions to the challenges presented by our current housing stock. Here are the main obstacles to lowering the impact on air quality caused by Britain’s houses, and how they can be overcome.

Challenge 1 - Waste less heat

There are more than 28 million homes in Great Britain, of which about 20 million have cavity walls, 8.5m solid walls and 24 million have a loft.48 The uptake of energy efficiency measures over the last couple of decades has made a significant contribution to the fall in gas demand since the early 2000s, with 70% of properties with a cavity wall and the large majority of lofts having insulation. Thicker loft insulation can cut heating consumption by 2%, whilst cavity wall insulation can deliver a further 7% saving and solid wall insulation can reduce consumption by around 12%.

However, there remain considerable opportunities to improve the fabric efficiency of the existing building stock. At the end of 2018, only 70% of properties with a cavity wall were insulated, leaving around 5 million cavity walls remaining to be insulated and, whilst most households have some degree of loft insulation, only 66% of homes have insulation of 125mm or more.<sup>50</sup> Very little progress has been made in installing solid wall insulation with less than 10% of the housing stock completed.

Over the last year, progress has stalled. In its 2019 progress report to Parliament, the CCC highlighted only 43,000 loft insulation measures had been installed against a target indicator of 545,000 measures. This picture is repeated for new cavity wall insulations (82,000 actual vs 200,000 target indicator) and solid wall insulation (18,000 actual vs 90,000 target indicator).51

However, there is limited funding available to help some groups of customers install insulation measures. E.ON, for example, offers free-of charge installation of cavity and loft insulation to eligible customers, as part of the Affordable Warmth Scheme52

It is clear that further action is needed to ensure that the existing housing stock is fit for the 21st century with modern levels of comfort.

Taking action to improve the fabric efficiency of buildings will directly reduce air pollutants arising from the existing heating systems of those buildings as a result of reducing heating demand whilst still meeting the desired level of comfort.

Challenge 2 - Promote low-emission Sources of heating

Heating our homes is the main cause of pollution associated with housing

Switching to more efficient and alternative sources of heating can make a big impact on air quality but the issue here is one of scale. By far the majority of homes in Britain have a gas boiler and either improving the efficiency of individual units or replacing them with something altogether more efficient will take significant effort and time.

Improving the energy efficiency of individual homes and heating systems can play a part in tackling issues around large scale emissions, local air quality and also fuel poverty. More efficient modern heating emits less and costs less to run.

The UK needs to do more to speed the growth of district heating networks at scale, both in new build developments, and where appropriate, retrofitted into existing communities. The ‘no regrets’ approach of district heating means a network is installed once, with just the single generation source evolving over time to make best use of newer, more efficient lower emitting technologies.

Inefficient boilers

At an individual level, gas boilers will have little impact on air quality across a whole community – even though the worst G-rated boilers may be as inefficient as 30%. Nevertheless, this changes at a community level. The London Environment Strategy recognises that, whilst road traffic in Greater London contributed slightly more than half of London’s NOx emissions in 2013, by 2020 nearly 50% of central London’s NOx emissions will be from domestic and commercial gas.53 Therefore, targeted measures to reduce the contributions from these sources will be important in continuing to improve air quality in London.

The challenge in the short term is to accelerate the move from lower rated boilers to at least an A+ model. This isn’t easy: the upfront cost of a replacement boiler can deter people – especially those in low-income households or rental landlords – who would otherwise stand to benefit in the long run.

Legislation is a proven way to improve standards in boilers. The Boiler Plus54 legislation mandated all gas boilers manufactured and installed in the UK to have an efficiency rating higher than 92%.55 Alongside this, the Energy-related Products (ErP) Directive required new boilers to comply with tighter NOx emission limits.

E.ON is offering discounted energy efficient A+ replacement boilers for anyone eligible under the Affordable Warmth Scheme. An estimated six million people could potentially benefit.56

Heat pumps

Electrification of heating provides additional air quality benefits for householders. Heat pumps act like a fridge in reverse, these thermal heat exchanges draw energy from the surrounding environment – air, ground or even water – and often provide around three times more heat for each unit of energy used to power it.57 They are growing in popularity: in Europe sales rose 13% in 2018, with 27,000 sold in the UK.58 Furthermore, they are being increasingly incorporated into the designs of new district heating networks.

The Committee on Climate Change has recognised in its recent net zero report to the Government that there is an important role for heat pumps and hybrid heat pumps.59 Innovation and large-scale deployment has the potential to reduce their cost, making them a realistic alternative for households and businesses. Heat pumps can be particularly apt for larger, older buildings. In fact, Historic England advises:

“Heat pumps are generally well-suited to historic buildings as they work efficiently when run on a constant low temperature, a method suited to buildings with thick masonry walls that are able to retain heat and release it slowly. This is referred to as having thermal mass.”60

They provide a viable alternative to traditional heating systems, especially for homes relying on oil, coal and LPG heating, and operate most effectively in well insulated buildings. Heat pumps can also play a key role in the design of new housing estates as well as operating in a hybrid mode with gas as a transition to a lower carbon energy system. The 2019 Spring Statement set out the Government’s intention to introduce a 2025 Future Homes

Standard which would prevent new homes being connected to the gas grid. Heat pumps will play a key role in helping housing developers comply with this standard.61 Increasingly heat pumps are being incorporated into the designs of district heating networks.

District heating

A way to avoid the inefficiencies of in-house boiler heating is to switch to district heating. In this model, heat is produced in localised hubs or energy centres and sent via superinsulated pipes to single apartment blocks, a network of local buildings, or even an entire community. Production at scale is more efficient and, in some circumstances, heat can be captured from industrial and commercial processes, avoiding waste and the need for first use generation.

Once the networks are built, the generation source within the energy centre can change as new technologies develop – and change more easily than retrofitting significant numbers of individual technologies in residential properties. For example, there are existing schemes which have moved from coal or oil to gas, biomass, biogas or even large-scale electrical heat pumps, further reducing emissions.

Elephant Park

One of the ways London is looking to reduce its emissions is through new low or even zero-carbon developments like Elephant Park, just south of the River Thames in Elephant and Castle.

Its innovative combined heat and power energy centre – installed and operated by E.ON – is designed to run partially on biogas and aims to use 100% renewable gas by 2023. Solar panels on the roofs will eventually generate 3% of Elephant Park’s total electricity.

With 3,000 sustainably designed homes as well as shops and space for offices, it will also feature plenty of outdoor spaces and the city’s largest new park in 70 years, increasing the area’s beauty and offsetting carbon emissions.

Heating empty houses

The Energy Saving Trust is vocal about ending the habit of keeping heating on when no one is home.62 The problem tends to be basic human nature and a love of routine: households set heating schedules via a timer or to hit a fixed temperature, so the heat comes on whether it is needed or not. Individual radiator valves offer the chance to turn off the heating in unused rooms, but, again, these require active attention from householders.

Smartphone energy control apps bring intelligent micro-management to heating, for example connecting the homeowner’s smartphone to a Wi-Fi-enabled thermostat to allow remote control of heat settings.

Apps can use geolocation to identify if anyone is home – with the heating turning on automatically when the first person heads back home. Furthermore, smart radiator thermostatic valves make it possible to control the heat in each room of the house remotely.

Wood stoves cause dirty air

In the opening chapter of Bleak House, Charles Dickens wrote of London in the age of coal and wood fires:

“Smoke lowering down from chimney pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun... fog everywhere.”

Domestic wood or coal burning stoves and open fires remain popular, present in one in ten UK households. It is estimated that these home fires cause 40% of the damaging particulate matter in the UK,63 three times more than road transport.

Open fires are often an aesthetic choice as much as a heating one. Fires and wood stoves make a house feel like a home. However, education around the air pollution caused by such stoves could encourage homeowners to reduce the frequency of their fires, to lower the impact.

Education around fuel types is also needed; wet wood and coal pollute far more than seasoned, dry wood.64 The Woodsure approved scheme guarantees logs have a moisture content lower than 20% – consumers may benefit from learning more about this scheme. The EU Ecodesign standards65 for stoves, which come into force in 2022, raise standards, but there is an opportunity to impose even higher efficiency standards on stoves.

Challenge 3 - Switch to zero emissions electricity

As we move to an energy system which is more electricity driven than in the past, it is important to ensure the way we produce electricity does not harm the environment from either a greenhouse gas or air quality perspective. The use of fossil fuels for generating electricity produces NOx emissions, which when combined with refineries makes up around 22% of the total NOx emissions.66

Increasing the deployment of renewable generation capacity, both at an industrial scale and also on rooftops all across the UK, will help to reduce the residual demand for fossil fuel based generation, directly contributing to further reductions in NOx emissions over the longer term and across the wider geographical area.

Phasing out coal fired power stations by 2025 and continuing the path of decarbonisation of the electricity system to 2030 will help to play an important role in reducing the emissions of air pollutants. It is important for public policy to encourage the deployment of the most cost effective renewable technologies such as solar, so that the significant uptake of solar we have seen from households since 2010 can continue into the next decade, allowing more customers to have an important stake in our future energy system.67 Technology development is also allowing for more of the electricity produced by solar to be utilised within the home, as battery costs have fallen considerably over time.68

Optimisation of solar panels will unlock further opportunities to reduce some of the key air pollutants.

The solution: with solar PV, houses are able to generate up to 30% more power than they typically use.69 Domestic batteries from 2.4kWh upwards can store power for use within the property at times more convenient to owners, increasing the potential and financial attractiveness of solar. In the absence of a Feed-in Tariff support system, some energy companies are offering householders the chance to sell excess energy to the utility provider for a profit. Meanwhile, Government proposals for a Smart Export Guarantee will re-introduce a financial support system for customers installing solar panels so that they receive a price for exporting any surplus electricity back to the grid. Additionally to that, new build housing developers should be encouraged to fit solar PV to ensure all new developments are future proofed, as is the case with the regulations in Scotland.70

The solutions are here. Let’s implement them.

Homes in Britain are improving, but more can be done to help them become more efficient, while contributing to cleaner air. Domestic energy consumption71 has fallen 17% from 2002 to 2017. The National Infrastructure Commission says 21,000 energy efficient measures should be installed a week.72

Progress under current Government energy efficiency targets is only 9,000.73

Source: Reducing UK Emissions parliamentary report 2018

Source: 2018 Progress Report to Parliament76

Energy efficiency is vital to cutting the costs of energy for homes and businesses and is a cost-effective method of reducing our carbon emissions. In spite of this, and the inclusion of energy efficiency targets in the Clean Growth Strategy, the current rate of improvements to buildings is far too slow.

Rachel Reeves MP, BEIS Committee Chair 74

Share to

Sustainable homes

Find out the many ways in which you can create a more sustainable home and reduce your carbon footprint.

The white paper - an introduction

The white paper - a foreword from the CEO

Solutions for workplaces

Solutions for cities and communities